What Is Bitcoin Mining? Understanding BTC Network Security and the Issuance Mechanism

Understanding Bitcoin mining helps clarify how a decentralized network can operate securely and enforce rules without any central authority. By examining what mining is, how it works, how it supports security, and where its structural limitations lie, we can better understand the core logic that underpins the Bitcoin network.

What Is BTC Mining? The Core Role Within the Bitcoin Network

BTC mining refers to the process by which network participants contribute computational power to validate transactions and generate new blocks, earning block rewards and transaction fees in return. In Bitcoin, mining is not “currency production” in the traditional sense. Rather, it is a foundational mechanism that maintains ledger consistency and enforces monetary rules in a decentralized environment. Miners do not control the network. Their role is closer to that of open, replaceable system maintainers.

From a functional perspective, mining fulfills three indispensable roles in the operation of the Bitcoin network.

First, miners validate transactions, ensuring that each one complies with protocol rules. This includes verifying the authenticity of digital signatures, confirming that balances are sufficient, and preventing any instance of double spending.

Second, once transactions pass validation, miners package them into candidate blocks according to the protocol’s specified format. This process organizes otherwise scattered transaction records into a structured and ordered block.

Finally, through computational competition under the Proof of Work mechanism, miners compete openly and unpredictably for the right to add the next block. The outcome determines which block the entire network will accept and append to the blockchain.

This competition-based approach to block production, rather than one based on authorization, is a defining feature of Bitcoin’s decentralization. Any participant who meets the protocol’s requirements can join the mining process without seeking permission and attempt to contribute to ledger maintenance. Because block production rights do not depend on any specific institution, identity, or trust relationship, the Bitcoin network can operate globally, sustaining ledger consistency and enforceable rules even in the absence of a central coordinating authority.

What Core Problems Does BTC Mining Solve?

In an open, permissionless decentralized network, the central challenge is how geographically distributed nodes can agree on a single version of the ledger. The original design goals of BTC mining can be summarized in three core questions:

Who gets to record transactions

Which version of the ledger should the entire network accept

How to prevent malicious behavior

Without a mining mechanism, any node could repeatedly broadcast conflicting transactions at low cost or even attempt to rewrite transaction history, making ledger consistency impossible to maintain. By introducing Proof of Work, Bitcoin ties block production rights to verifiable computational cost. Acquiring the right to add a block requires real-world resources, which limits the space for malicious activity at its source.

Miners only receive block rewards and transaction fees if they follow protocol rules, include valid transactions, and produce legitimate blocks. Attempting to cheat or alter history requires enormous computational expenditure and may still fail if the network rejects the altered chain. By making malicious behavior expensive and honest participation comparatively efficient, Bitcoin achieves long-term ledger consensus without centralized management.

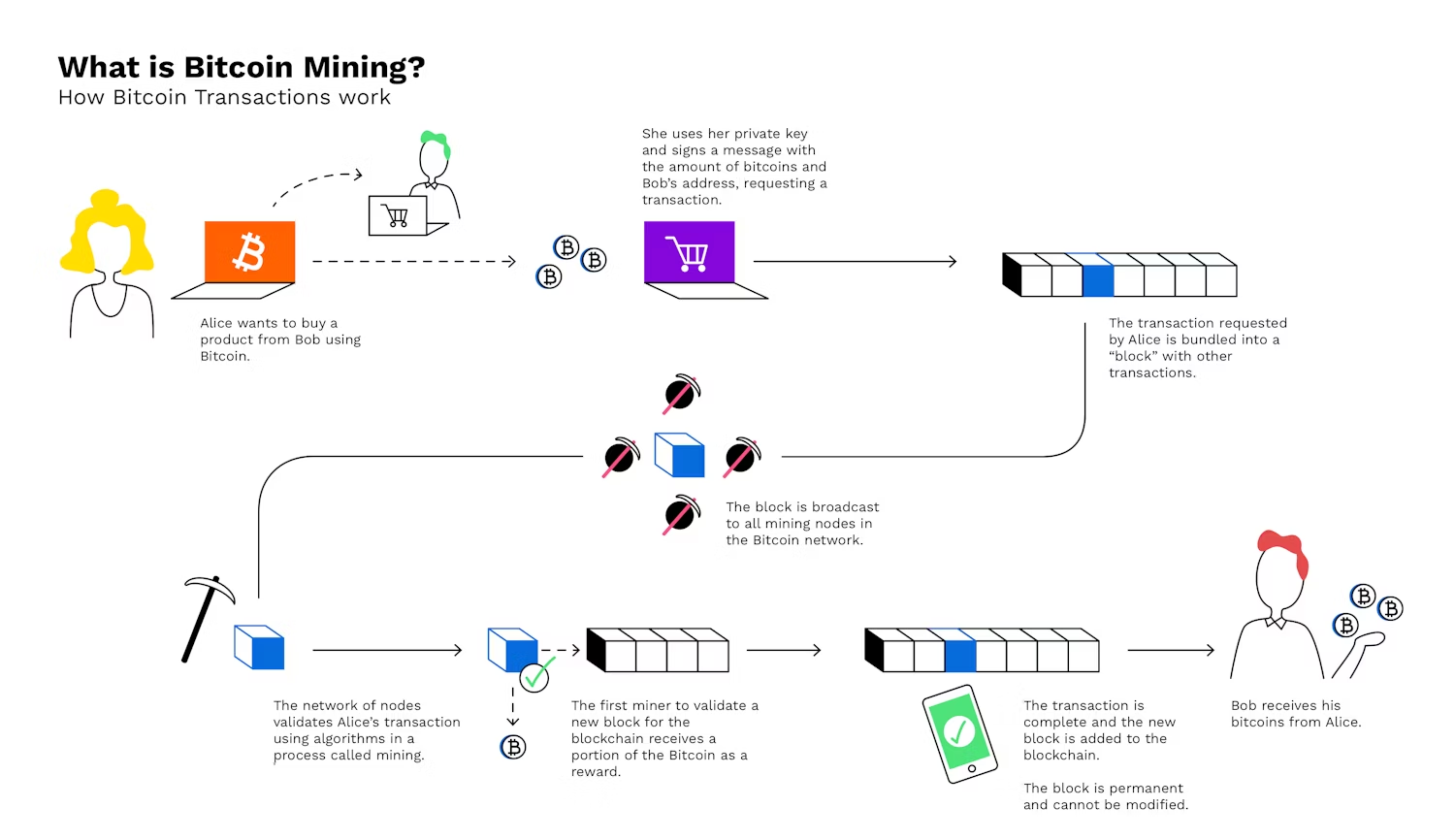

How the BTC Mining Process Works

From a technical standpoint, BTC mining is not a one-time calculation. It is an ongoing, network-wide competitive cycle. Each round centers on the creation of a new block. At its core, miners are competing through computation for a single opportunity to have their block recognized by the network.

The process typically begins with transaction collection. Miners select unconfirmed transactions from the mempool and conduct preliminary checks to ensure the transaction format is correct, the digital signatures are valid, and the sender’s account holds sufficient balance. This step prevents invalid or malicious transactions from entering a block and safeguards the credibility of the ledger at its source.

After validation, miners construct a candidate block according to protocol rules and begin calculating its hash based on the block header information. Because Bitcoin uses a Proof of Work mechanism, miners must repeatedly adjust the block’s nonce and perform continuous hash calculations, searching for a result that meets the current difficulty target. There are no shortcuts in this process. It depends entirely on computational power, and the outcome is highly probabilistic.

Once a miner finds a hash that satisfies the required condition, the new block is broadcast to the entire network. Other nodes independently verify the legitimacy of the transactions within the block, confirm the correctness of the hash computation, and check compliance with consensus rules. Only after passing these validations is the new block officially added to the blockchain, forming the foundation for subsequent blocks.

This process ensures that block production does not rely on centralized decision-making. Instead, outcomes emerge through open competition. The right to add a block is both probabilistic and costly, which helps the Bitcoin network maintain ledger consistency in an open environment and prevents any single entity from controlling block generation over time.

The Role of Proof of Work (PoW) in BTC Mining

Proof of Work, or PoW, is the core mechanism that enables BTC mining to function and the foundational tool through which Bitcoin achieves decentralized consensus. Its essence is not about proving how many computational tasks were completed. Rather, it demonstrates that a participant has expended real, verifiable, and non-forgeable resources in competing for the right to add a block. These resources primarily take the form of computational power and energy consumption, ensuring that block production rights cannot be obtained arbitrarily.

Under the PoW mechanism, every miner must repeatedly attempt hash calculations, searching for a result that meets the current difficulty target. Because hash functions are inherently unpredictable, miners cannot calculate a shortcut to success. They must rely on sustained computation. This process naturally exhibits a “hard to compute, easy to verify” structure. Finding a valid result requires extensive trial and error, while verifying its correctness requires only a single calculation. This asymmetry allows network nodes to validate new blocks at extremely low cost.

Another key feature of PoW is its role in protecting historical records. Once a block is added to the blockchain, any attempt to alter its contents would change its hash, forcing the attacker to redo the Proof of Work for that block and every block that follows it. As total network hash power continues to grow, the cost of rewriting history accumulates rapidly over time, making such attempts economically unrealistic in practice.

By tightly binding block production rights, chronological order, and resource expenditure, PoW enables Bitcoin’s ledger to form a stable historical consensus. Once a block has been confirmed by multiple subsequent blocks, the probability of reversal declines significantly. This mechanism does not depend on trusting any specific node or organization. Instead, through transparent rules and economic cost, it achieves long-term consistency and security in an open network.

BTC Mining, Block Rewards, and the Issuance Mechanism

BTC’s issuance mechanism is not controlled by any centralized authority. It is written directly into the Bitcoin protocol and automatically executed through the mining process. Each time a new block is successfully mined, the system issues a block reward to the miner according to predefined rules and allows the miner to collect the transaction fees included in that block. In this way, monetary issuance, ledger maintenance, and network security are unified at the protocol level.

Bitcoin’s monetary rules are highly explicit and independently verifiable. The total supply is capped at approximately 21 million coins, and any node can verify whether this rule is being followed. The block reward is reduced by half roughly every 210,000 blocks, gradually slowing the pace of new issuance over time. The entire issuance schedule is transparent and predictable at the protocol level, independent of macroeconomic conditions or discretionary human decisions. This determinism is one of the defining differences between Bitcoin and traditional monetary systems.

From an incentive perspective, block rewards serve as the primary economic motivation for miners, especially in the early stages of the network when newly issued BTC provided strong security incentives. As time passes and block rewards decline, transaction fees are expected to account for a growing share of miner revenue. Embedded in this design is a long-term assumption: as new issuance approaches zero, genuine transaction demand will continue to provide sufficient economic incentives to sustain network security.

More importantly, this structure tightly binds monetary issuance to system maintenance. Miners can earn rewards only by following protocol rules and safeguarding ledger integrity. Any attempt to undermine consensus or rewrite history cannot be sustained economically. As the network’s scale and value grow, the cost of securing it rises in parallel, forming a relatively stable long-term incentive loop.

How the Difficulty Adjustment Mechanism Maintains BTC Network Stability

The Bitcoin network uses a difficulty adjustment mechanism to respond to ongoing changes in total network hash power, maintaining a steady block production rhythm and overall system stability. Under the protocol rules, mining difficulty automatically adjusts roughly every 2,016 blocks, or about every two weeks. The goal is to keep the average time required to produce a new block close to ten minutes over the long term. This process requires no human intervention. All nodes independently execute the adjustment according to transparent, predefined rules.

At its core, difficulty adjustment decouples block production speed from fluctuations in hash power. If total network hash power increases and difficulty remains unchanged, new blocks would be mined too quickly, disrupting both the issuance schedule and the pace of ledger growth. In response, the system raises difficulty, increasing the computational cost required to mine each block and bringing block intervals back toward the target range. Conversely, if hash power declines or miners exit the network, the system lowers the difficulty of preventing block production from slowing excessively, ensuring the network continues to function smoothly.

This mechanism carries important implications for both network security and economic incentives. By dynamically adjusting difficulty, Bitcoin can maintain a relatively stable operating rhythm even in environments where hash power fluctuates significantly. It helps prevent uncontrolled inflation that might result from excessive concentration of hash power and reduces the risk of transaction congestion or consensus stagnation following sudden drops in participation. At the same time, difficulty adjustment keeps mining costs aligned with network scale, making it difficult for an attacker who briefly acquires substantial hash power to destabilize the system over the long term.

From a broader design perspective, the difficulty adjustment mechanism is one of the key institutional safeguards that allows Bitcoin to operate sustainably over time. The network does not depend on a fixed number of participants or a stable level of computational power. Instead, it relies on adaptive rules to respond to changing external conditions. By replacing discretionary control with protocol-driven adjustments, Bitcoin further reinforces its stability and resilience as a decentralized system.

How BTC Mining Secures the Network

BTC mining forms the economic foundation of Bitcoin’s network security. Under the Proof of Work mechanism, ledger security does not depend on trusting any central authority. Instead, it rests on real, continuous, and measurable resource expenditure. Any attacker attempting to alter a historical block must redo the PoW for that block and every subsequent block, while maintaining more hash power than the rest of the network throughout the process.

In practical terms, the barriers to such an attack are extremely high. First, acquiring enough hash power to compete with the entire network requires massive investment in hardware and energy, and these costs rise alongside the network’s scale. Second, even if an attacker temporarily amasses substantial hash power, they must sustain that advantage continuously. If their computational share falls short, the attack chain will quickly be rejected by the network. More importantly, a successful attack does not necessarily generate profit. By undermining network credibility, the attacker may reduce the value of their own BTC holdings.

Within this structure of high costs and uncertain returns, Bitcoin establishes a stable security equilibrium. From a game-theoretic perspective, rational miners are more likely to follow protocol rules and participate honestly in order to earn ongoing block rewards and transaction fees, rather than risk engaging in destructive attacks. As time passes and confirmation counts increase, the economic cost of reversing historical blocks rises exponentially, rendering ledger entries effectively irreversible in practice.

This security model, grounded in economic incentives rather than coercive authority, is one of the defining distinctions between Bitcoin and traditional financial systems. By directly tying network security to resource expenditure and aligned incentives, Bitcoin enables long-term stable operation in an open environment without centralized control.

Structural Limitations and Controversies in BTC Mining

From an operational perspective, BTC mining has provided Bitcoin with a highly robust security foundation. Yet over time, its continued development has also revealed structural limitations and sparked ongoing debate. These issues do not stem from a single design flaw. Rather, they arise from how the Proof of Work mechanism interacts with real-world technological, economic, and resource constraints.

On one hand, as mining difficulty has steadily increased, it has become nearly impossible for individual users to participate using general-purpose hardware. Specialized ASIC machines, large-scale mining facilities, and access to low-cost energy have significantly raised the barrier to entry. Under competitive pressure, hash power has gradually concentrated in large mining pools and professional operators, creating a trend toward concentration at the computational level. Although mining pools do not directly control miners’ assets and participants can switch pools freely, short-term imbalances in hash power distribution are still viewed as potential systemic risks.

On the other hand, BTC mining’s continuous energy consumption has fueled widespread debate over environmental impact and efficiency. Proof of Work introduces real physical costs to deter malicious behavior, but this also means that network security depends on ongoing electricity and hardware expenditure. Depending on the perspective, this feature is seen either as a necessary cost of anchoring security in the physical world or as a source of relatively low resource efficiency. Much of the controversy focuses on energy composition, usage scenarios, and the allocation of social costs, rather than on technical feasibility alone.

It is important to emphasize that these debates do not invalidate the effectiveness of the BTC mining mechanism itself. Instead, they highlight the deliberate trade-offs embedded in Bitcoin’s design. The system prioritizes security and censorship resistance in an open network over minimizing energy consumption or maximizing efficiency. In a permissionless global system where anyone can participate, it is difficult to simultaneously optimize security, efficiency, and sustainability. Bitcoin places security first and accepts the practical constraints that follow.

For this reason, discussions surrounding mining are ultimately discussions about Bitcoin’s underlying value hierarchy. It is not attempting to become the most energy-efficient system. Rather, it seeks to function as a decentralized ledger capable of operating stably over the long term without a central arbiter.

Summary

BTC mining is not merely a “coin production” process. It is an integrated mechanism that unifies consensus, security, and issuance rules. Through Proof of Work, difficulty adjustment, and incentive alignment, Bitcoin achieves stable operation without centralized management. Understanding the logic of mining is key to understanding how Bitcoin functions as a durable decentralized network.

FAQ

Is BTC mining equivalent to creating value?

Mining itself does not generate external demand, but by maintaining the ledger and securing the network, it provides foundational services.

Can ordinary users still participate in BTC mining?

Technically, participation remains open, but economically it has become highly specialized.

Does mining still matter once BTC issuance ends?

After block rewards disappear, transaction fees are expected to become the primary incentive source, and mining will continue to perform its security function.

Related Articles

In-depth Explanation of Yala: Building a Modular DeFi Yield Aggregator with $YU Stablecoin as a Medium

BTC and Projects in The BRC-20 Ecosystem

What Is a Cold Wallet?

Blockchain Profitability & Issuance - Does It Matter?

What is the Altcoin Season Index?