bid price vs ask

What Are Bid Price and Ask Price?

The bid price represents the highest price a buyer is currently willing to pay for an asset, while the ask price is the lowest price a seller is willing to accept. The difference between these two prices is known as the "spread," which acts as a hidden transaction cost.

On a centralized exchange order book, the bid price corresponds to the “best bid” and the ask price to the “best ask.” For example, if the best bid for a trading pair is 100 and the best ask is 101, the spread is 1. This means that executing a market buy will match you with the nearest available ask price, not the bid price.

The size of the spread is influenced by market activity, market maker quotes, and risk expectations. Major tokens and periods of high activity tend to have tighter spreads, while less-traded assets or times of major news announcements often see wider spreads.

Why Is There Always a Difference Between Bid and Ask Prices?

The spread between bid and ask prices compensates market makers and liquidity providers for inventory, capital, and volatility risk, as well as operational costs.

Market makers place orders on both sides to provide immediate tradability. They take on risks from price volatility and inventory imbalance. A larger spread allows for greater risk coverage; a smaller spread increases trading efficiency but reduces profit margins for market makers.

During periods of intense news or increased volatility, uncertainty rises—bids retreat lower, asks move higher, and spreads widen. Conversely, stable or highly liquid assets usually feature tighter spreads.

How Are Bid and Ask Prices Formed on Centralized Exchanges?

Bid and ask prices are determined by the lineup of orders on the order book. Limit orders set specific prices, while market orders "take" available liquidity by matching with counterparty offers.

A “limit order” lets you set your desired price and wait for a match—like posting a sign in the market. A “market order” executes immediately at the best available counterparty price. Limit orders provide liquidity; market orders consume liquidity.

Some platforms refer to liquidity providers as “Makers” and liquidity takers as “Takers,” each with different fee structures. The highest bid in the buy queue becomes the new bid price; the lowest ask in the sell queue becomes the new ask price.

For example: If the best ask is 101 with only 10 units available, and you place a market order to buy 20 units, the first 10 fill at 101, and the next 10 fill at higher ask levels, resulting in an average execution price above 101. This extra cost is called “slippage.”

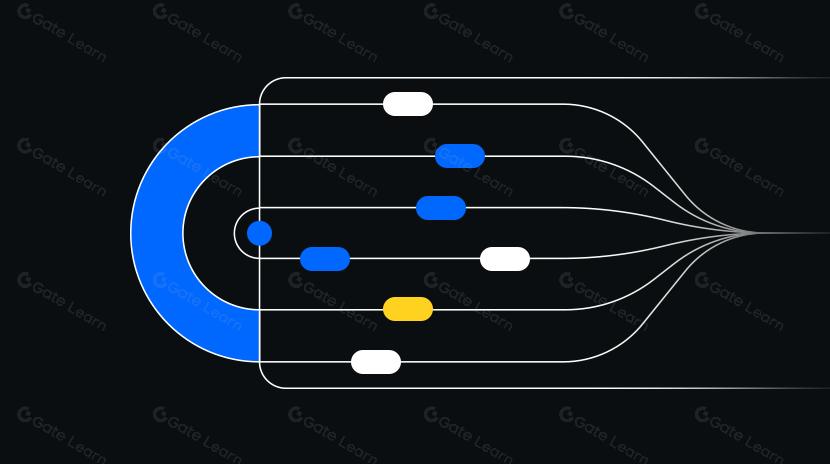

How Are Bid and Ask Prices Reflected on Decentralized Exchanges?

On AMM-based (Automated Market Maker) decentralized exchanges (DEXes), there is no traditional order book with best bid/ask prices. Instead, bid and ask prices are determined by the ratio of two assets in a liquidity pool, and trades move pool prices, creating “slippage.”

Slippage refers to the difference between your actual average execution price and the quoted reference price. Larger orders or smaller pools result in greater slippage.

For instance, in a constant product pool with 1,000 ETH and 2,000,000 USDC (implying a reference price of 2,000 USDC/ETH), buying 10 ETH reduces ETH in the pool and increases USDC, raising the equilibrium price. The trade might require about 20,202 USDC—an average price of approximately 2,020.2 USDC/ETH—resulting in roughly 1% slippage (for illustration).

Additionally, AMMs charge pool fees, affecting your final token amount. Thus, on DEXes, bid/ask prices are more like an estimated quote plus price impact and fees.

How Do Bid-Ask Prices Affect Trading Costs?

The spread between bid and ask prices, along with slippage and trading fees, make up your true transaction costs. Even if not immediately obvious, these costs directly affect your net execution amount and average price.

For example, in an order book scenario with a best bid of 100 and best ask of 101: buying at market executes at 101; selling at market immediately after executes at 100—resulting in a loss of 1 (excluding fees). This is known as “crossing the spread.”

In AMM examples, large orders push up average buy prices or push down average sell prices—even without visible book prices. Slippage and fees create an equivalent “bid-ask spread.”

Where Can You View Bid and Ask Prices on Gate and How Do You Place Orders?

On Gate’s spot trading page, you can view bid and ask prices directly in the order book and control your costs through order placement.

Step 1: Select your trading pair on the page. Observe the top of the right-hand order book for the best ask (lowest selling price) and the bottom for the best bid (highest buying price). Mid-prices are for reference only and may not be immediately executable.

Step 2: To control execution price, choose “limit order” and place your order near the current bid or ask. Waiting in the queue for a match can reduce spread costs.

Step 3: For immediate execution, select “market order.” The system matches you with the best available ask (for buys) or bid (for sells). Note that market orders can incur significant slippage.

Step 4: Review “depth” or “trade history” to assess if your order size will clear multiple price levels. If so, consider splitting orders to minimize slippage.

Step 5: If available, enable options like “post-only” or “maker-only.” This prevents your order from immediately executing as a “Taker,” helping to reduce fees and spread costs but potentially increasing wait times.

Risk Warning: Using market orders or trading during low liquidity or volatile periods can result in significant slippage or partial fills. Balance speed against cost accordingly.

How Should You Choose Bid or Ask Price During Volatile Markets?

During periods of rapid volatility, bid and ask prices change quickly—using market orders can lead to high costs.

Step 1: Prefer limit orders with stop-loss/take-profit conditions to set your maximum acceptable price and avoid unexpected slippage.

Step 2: Break up large trades into multiple smaller ones over time or at different price levels to reduce impact on bid-ask prices and average cost deviation.

Step 3: On DEXes, set lower “slippage tolerance” to avoid executing far from expected prices due to volatility; adjust if failures are frequent.

Step 4: Avoid large market orders across multiple price levels before or after major data releases; wait for spreads to tighten and depth to recover before executing.

How Are Bid-Ask Prices Related to Liquidity?

High liquidity results in tighter bid-ask spreads and deeper order books or liquidity pools. Greater depth absorbs larger orders with less impact on price.

On centralized exchanges, deep buy/sell queues mean narrower spreads and minimal impact from market orders. On DEX pools, larger pool size and more active trading pairs minimize price movement per trade.

Conversely, illiquid tokens or obscure pairs often have wider spreads and greater slippage. Assessing depth and pool size before placing an order is key to cost control.

Common Misconceptions About Bid-Ask Prices

Misconception 1: Assuming the latest transaction price equals an executable price. In reality, you buy at the current ask and sell at the current bid—the last traded price is just historical data.

Misconception 2: Believing “zero fees” means “zero cost.” Even without trading fees, crossing the spread and incurring slippage still impact your costs.

Misconception 3: Always using market orders for speed. While speed matters in some cases, insufficient depth or high volatility can dramatically increase costs.

Misconception 4: Ignoring order size impact. In identical markets, small orders experience less slippage than large ones—splitting trades and monitoring depth can significantly improve average execution prices.

Key Takeaways for Bid Price and Ask Price

Bid and ask prices form the foundation of all trades; their spread and associated slippage are hidden costs. Centralized order books and decentralized AMMs reflect these costs differently. Monitoring depth, choosing appropriate order types, managing trade size, and setting slippage tolerance can greatly improve execution quality on platforms like Gate. Always check bid price, ask price, and depth before placing any trade.

FAQ

What is the difference between bid and ask prices called? How does it impact my trading costs?

The difference is known as the “spread” or “bid-ask spread,” which is a source of income for exchanges or market makers. The larger the spread, the higher your transaction cost—buying means paying more; selling means receiving less. Even without fees, this cost exists on every trade (“getting clipped”). On highly liquid assets, spreads are often just a few basis points; for illiquid tokens they may exceed 1%, significantly eating into profits.

Why does the bid price sometimes become the ask price (or vice versa)?

This happens because buyer and seller roles switch. When you want to buy, you see seller prices (asks); when you want to sell, you see buyer prices (bids). Put simply: The bid is what someone will pay you if you sell; the ask is what someone will sell to you if you buy—these represent opposing sides of every trade.

During fast-moving markets, should I use the bid or ask price when placing orders to avoid slippage?

In fast markets, use limit orders near your target price for control. To ensure execution, place buy limit orders near bids (willing to pay a small premium) or sell limit orders near asks (willing to accept a slight discount). But if prices move away from your order, it might never fill. The safest approach is using Gate’s advanced order tools—set reasonable ranges and slippage limits so the system executes at optimal prices automatically.

Why are bid and ask prices different for the same token on Gate versus other exchanges?

Spreads vary based on liquidity depth and market-making mechanisms. Major exchanges like Gate have high trading volume with many participants—spreads are typically tight. Smaller platforms with poor liquidity may have much wider spreads. Arbitrage traders exploit these differences across exchanges for profit. Choosing exchanges with strong liquidity greatly reduces your trading costs.

Are bid-ask concepts in crypto markets identical to those in forex?

The core meaning is similar but practical contexts differ slightly. In forex, spreads measure exchange rate volatility and transaction costs; in crypto markets, you must also factor in token liquidity fluctuations. In both cases—the bid is always lower than the ask—this difference funds market makers or exchanges. Understanding this helps you accurately calculate true trading costs in any market environment.

Related Articles

Exploring 8 Major DEX Aggregators: Engines Driving Efficiency and Liquidity in the Crypto Market

What Is Copy Trading And How To Use It?