Is the Fed's monthly purchase of 40 billion in government bonds QE? Powell clarifies: This is not quantitative easing

The Federal Reserve purchases $40 billion in U.S. Treasuries each month, and the market is heralding the return of quantitative easing (QE). However, this move by Powell is not aimed at stimulating the economy but at preventing issues in the financial system’s operation. This is the Reserve Management Purchase Program (RMP), which differs fundamentally from traditional QE in mechanism, purpose, and effect. Although technically RMP meets the definition of QE, its role is stabilizing rather than stimulative. Understanding the difference between the two is key to judging market trends.

The True Definition of QE and the Three Mechanical Conditions

To strictly define quantitative easing and distinguish it from standard open market operations, certain conditions must be met. First, at the mechanism level, the central bank creates new reserve funds to purchase assets, typically government bonds. Second, the scale requirement: the purchase volume must be significant relative to the total market size, aiming to inject substantial liquidity into the system rather than fine-tune interest rates. Third, the target difference: standard policy adjusts supply to achieve a specific interest rate, whereas QE purchases a set amount of assets regardless of how the final interest rate changes.

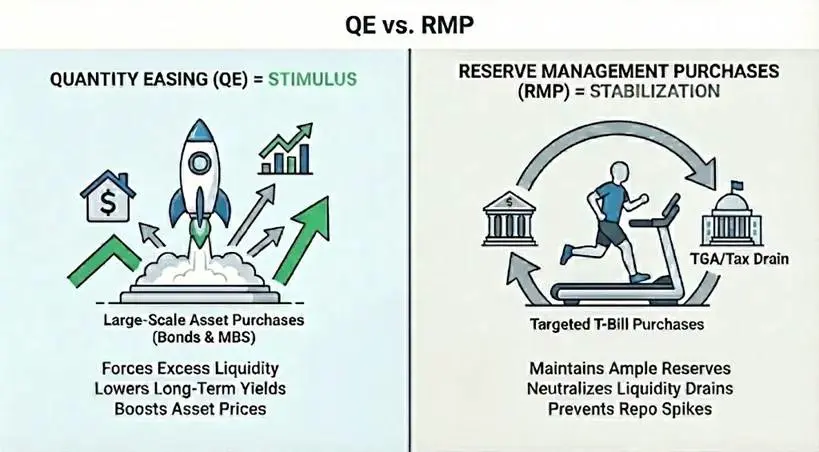

Beyond these three mechanical conditions, QE also has a functional condition: positive net liquidity. The speed of asset purchases must exceed the growth rate of non-reserve liabilities (such as currency and the Treasury General Account). The goal is to force excess liquidity into the system, not just provide the necessary liquidity. This excess liquidity pushes up asset prices, lowers yields, and forces investors toward higher-risk assets.

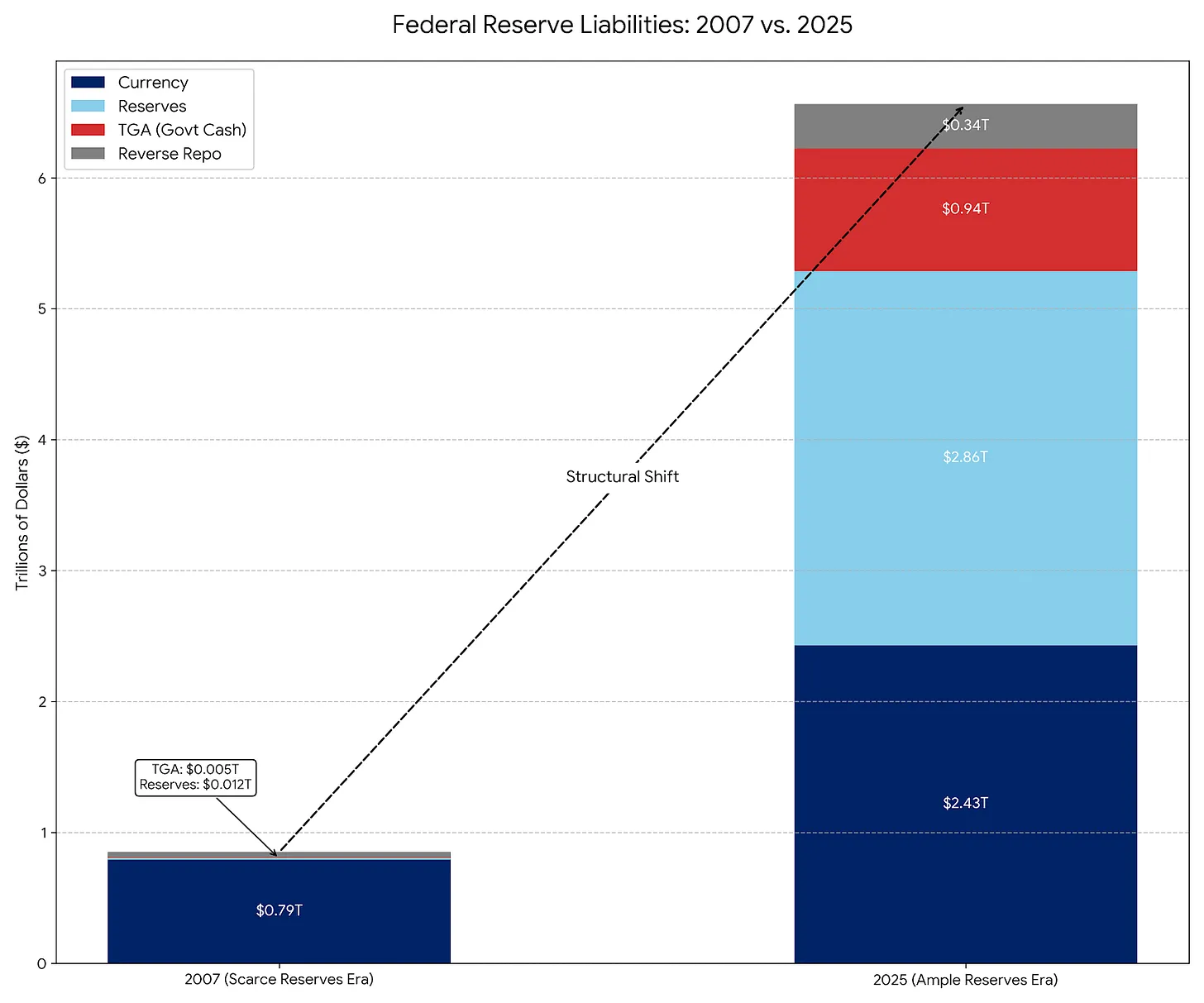

A classic example of traditional QE is the three rounds of quantitative easing after the 2008 financial crisis. The Federal Reserve massively bought government bonds and mortgage-backed securities (MBS), expanding its balance sheet from $900 billion to $4.5 trillion. These purchases not only provided liquidity but, more importantly, lowered long-term interest rates, stimulating economic activity. This stimulative effect is the core standard for judging whether it is QE.

The Fundamental Difference Between QE and RMP Lies in Purpose

RMP (Reserve Management Purchase Program) is essentially the modern successor to Permanent Open Market Operations (POMO). Before 2008, the Fed’s main liabilities were physical currency in circulation, with fewer and more predictable other liabilities. Under POMO, the Fed’s securities purchases were merely to meet the public’s gradual demand for physical cash, calibrated to be liquidity-neutral.

Today, physical currency accounts for only a small part of the Fed’s liabilities, which are mainly dominated by large and volatile accounts such as the Treasury General Account (TGA) and bank reserves. Under RMP, the Fed buys short-term government bonds to buffer these fluctuations and continuously maintain ample reserve supply. Similar to POMO, RMP is designed to be liquidity-neutral, not aimed at net liquidity injection like QE.

Technically, RMP meets the mechanical definition of QE: large-scale asset purchases via new reserves ($40 billion per month), with the goal being quantity rather than price. But functionally, RMP is not QE. RMP does not significantly loosen the financial environment but instead prevents further tightening during events like TGA replenishment. Since the economy naturally drains liquidity over time, RMP must operate continuously to maintain the status quo, which is entirely different from the stimulative nature of QE.

The True Nature of RMP: Liquidity Crisis During Tax Season

The reason Powell implemented RMP is to address a specific financial system issue: liquidity withdrawal from the TGA. The operation is straightforward: tax payments withdraw liquidity from the banking system, while the TGA resides outside the commercial banking system. The impact of this fund transfer is that if reserve levels fall too low, banks will stop lending to each other, potentially triggering a repo market crisis.

The Fed initiates RMP to offset this liquidity withdrawal. They create $40 billion in new reserves to replace the liquidity that will be locked in the TGA. Without RMP, tax payments would tighten the financial environment (a negative). With RMP, the impact of tax payments is neutralized. This neutralizing effect, rather than stimulation, is the key to distinguishing RMP from QE.

Three Main Factors Behind the Activation of RMP

TGA Liquidity Withdrawal: When individuals and businesses pay taxes, cash transfers from bank accounts to the Treasury General Account, draining liquidity from the banking system.

Repo Market Risk: If reserves fall too low, banks may cease lending to each other, potentially triggering a repo crisis similar to September 2019.

Tax Season Timing: December and April are the main tax deadlines, periods when liquidity withdrawal is most severe.

When RMP Will Turn Into Real QE

RMP becomes full-fledged QE if one of two variables changes. The first is the duration: if RMP begins purchasing long-term government bonds or mortgage-backed securities (MBS), it becomes QE. Doing so removes interest rate risk from the market, lowers yields, and pushes investors toward higher-risk assets, thereby raising asset prices. This asset price boost is a typical feature of QE.

The second variable is the scale: if the natural demand for reserves slows (e.g., TGA stops growing), but the Fed continues purchasing $40 billion per month, RMP will turn into QE. At that point, the Fed injects excess liquidity into the financial system beyond demand, which will inevitably flow into financial asset markets, pushing up prices of stocks, bonds, and other risk assets.

Monitoring these two variables is the practical way to judge whether RMP is transforming into QE. If the assets targeted by RMP expand from short-term to long-term bonds or MBS, or if the scale exceeds liquidity needs, these are clear signals of QE. Before these signals appear, equating RMP with QE is a misreading of the policy’s essence.

Market Impact: Stabilizer Rather Than Stimulator

RMP aims to prevent liquidity withdrawal during tax season from impacting asset prices. Although technically neutral, it sends a psychological signal to the market: “The Fed’s safety net” has been activated. This announcement is a net positive for risk assets, providing a gentle tailwind. By committing to $40 billion monthly purchases, the Fed effectively provides a floor for bank system liquidity, eliminating tail risks of repo crises.

However, RMP is a stabilizer, not a stimulator. Since RMP merely replaces liquidity withdrawn by the TGA rather than expanding the net monetary base, it should not be mistaken for systemic easing through genuine QE. Misreading this could lead investors to unrealistically expect asset prices to rise further.